John Eliot, known as the “Apostle to the Indians” (the Algonquian Indians in Massachusetts, America), was born in Widford in 1604 and baptised in the village church on 5th August of that year. His parents, Bennett Eliot and Letye Aggar were probably born and baptized in Widford (record keeping was not very consistent at that time), and we know they were married in Widford church on 20th October 1591. John was the fourth child of the marriage. Bennett Eliot was a Yeoman farmer (small landowner) and his extended family owned land not only in Widford but also in some of the surrounding villages, notably Hunsdon and Eastwick as well as Nazeing in Essex.

It was a time of great political and spiritual unease, especially in this area of East Hertfordshire and West Essex. The religious reforms and the growth of Protestantism on the continent of Europe had not made much of an impact on the English people in general until Henry VIII decided to break with Rome and declare himself the head of the Church in England. However, after this, while many welcomed the changes, such as the introduction of the English language into their services and the dissolution of many of the powerful monasteries, others were unconvinced. The radical changes meant that families were often driven apart by their beliefs. This was certainly true of Henry VIII’s own family: his son, Edward (VI), stayed true to the new Protestantism; his daughter, Edward’s elder half-sister, Mary (I), remained staunchly true to the Roman Catholic faith; his second daughter, Edward and Mary’s half-sister, Elizabeth (I), embraced the Protestant faith. As each of these children in turn became monarch, they brought their own religious convictions to the governance of the nation. These turbulent years bought many conflicts, conflicts which were still not resolved when the protestant James VI of Scotland was crowned James I of England on the death of Elizabeth I in 1603.

During most of these years the Lords of the Manor of Widford had been largely absentee landlords. Such authority that did exist would have been vested in the appointed Parish Priest. It is reasonable to assume that in Widford, as in many country parishes, change happened slowly, if at all; often, the old ways of life and worship were maintained despite the decisions of the monarchs and the lords. Having said that, it is perhaps noteworthy that in Widford in the year that saw the final legislation enacted to remove all of the Pope’s authority over the church in England (1536), the parish priest, Revd Fulco Brugg, resigned his post (that year or the following). We may surmise that Revd George Grantham, who succeeded him, was at least sympathetic to the changes – it is unlikely he would have been appointed to a living so close to one of Henry VIII’s homes if he were significantly hostile.

Shortly after John’s birth, the family moved to Nazeing where three more children were born. We do not know the reason for this relocation, but it is possible that religious convictions may have played a part. Little is known about Bennett and Letye Eliot’s personal life, except that they were recognised as people “full of prayer and piety.” It is possible they favoured a more Puritan form of worship and that Nazeing offered a community which was more congenial to them. The beliefs that John learnt from his parents formed his character and remained with him for the rest of his life. As an adult, reflecting on his parents’ devotion, he said, “I do see that it was a great favour of God unto me to season my first years with the fear of God, the word and prayer.”

At 14 years of age, he became a scholar in Jesus College in Cambridge. His father must have valued his son’s education, as before he died in 1621, he had made special provisions in his Will, so that the family would continue to support John in his studies. John passed his matriculation in 1619 and gained his Bachelor of Arts Degree in 1623. It was said that “he had a great facility for both the Latin and Greek languages”, and that he was “strongly inclined” towards some form of Christian ministry. However, unlike many other students, it appears he was not ordained into the English Church after completing his education. He returned to his family in Essex and took up a post as an assistant tutor at a school in Little Baddow, where he was much influenced by the teachings of the owner of the school, the Revd Thomas Hooker, a Puritan (later known as the Father of American democracy). He later wrote of his time in Little Baddow, “To this place was I called through the infinite riches of God’s mercy in Christ Jesus to my poor soul, for here the Lord said unto my dead soul ‘Live, live!’ and through the grace of God I do live for ever! When I came to this blessed family I then saw as never before the power of godliness in its lovely vigour and efficacy.”

During the seven years that followed, two important incidents occurred in his life. The first of these was his meeting his future wife, Miss Ann Mumford. Spellings of names were often inconsistent, so some records give her the surname Mountford and the Christian name Hannah. It is likely that her given name at birth was Hannah, but she preferred to go by the name Ann; certainly, records in Roxbury refer to her as Ann. The second important incident was his decision, at the age of 27, to join with other Pilgrims sailing to the Province of New England in what was then known as the “New World” (America). Before leaving, Eliot made a pledge to his friends and family that if they were to follow him, and had he not by then obtained a pastoral charge in one of the new settlements, he would become their minister.

Eliot travelled on the ship “The Lyon” with 60 other passengers. The ship docked in Boston harbour on 3rd November 1631 and he remained in Boston for the first year, acting as a temporary replacement pastor for a Mr Wilson. Within the year, friends and family members had joined him, including Ann Mumford, whom he married in October 1632. A short time later, on 5th November 1632, he was ordained as the First Minister for the Roxbury settlement. He was to remain there until his death, almost 60 years later.

In 1645, with the support of Captain John Johnson, who provided the land, and having persuaded almost all the landowners in Roxbury to underwrite the costs, Eliot founded Roxbury Latin School. He further persuaded them to defray tuition costs for poorer students so that all residents of Roxbury would have the opportunity to receive a high-quality education. In the 1660s, it was listed as one of Harvard College’s leading feeder schools and, because it did not close down during the American Revolution, has earned itself the title of the oldest school in continuous existence in North America.

Eliot was not only a clever man; he was extremely patient and worked hard to maintain a peaceful atmosphere in the settlement. His attitude, after the example of Christ, was “hear, forbear and forgive.” His many acts of charity were often to the detriment of his own family. His modesty and honesty were very conspicuous. It is conceivable that these qualities were instrumental in his having such a good rapport with the Algonquian tribes – he approached them as equals.

Eliot began to learn the Algonquian language in the early 1640s from a native servant named Cockenoe in Roxbury. He made Cockenhoe his interpreter, and in time grew sufficiently proficient in the language to begin preaching to the natives in their own tongue – starting in October 1646 with sermons in native dwellings in the woods in what is today the neighbourhood of Nonantum, Massachusetts.

His foremost desire, obviously, was that the people should come to know Christ Jesus as Lord and Saviour. The original charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company signed by Charles I in 1629 stated the settlers’ mission was essentially evangelical – that they “may win and incite the natives of the country, to the knowledge and obedience of the only true God and Saviour of mankind, and the Christian faith, which in our royal intention, and the adventurers’ free profession, is the principal end of this plantation.” The official 1629 seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company depicted an Indian crying out, “COME OVER AND HELP US” (cf. Acts 16:9). The Massachusetts state seal remains an iteration of the original even today. Eliot took the charter seriously and made an earnest effort to be faithful to the mission.

As part of his evangelistic work and resulting from his understanding of the Lordship of Christ, Eliot laboured for the education and earthly prosperity of the natives too. He believed that the Native American community would benefit from larger groupings and by learning more practical skills in addition to their hunting and subsistence farming. From the early 1640s, he helped them to form small villages. In each village was a workshop, granaries, plantations, a school and later a mission post. By 1661, Eliot had translated the New Testament and could preach to them fluently in their own language, and two years later he presented them with a translation of the Old Testament. The English House of Commons was so impressed with his work that funds were sent and a Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England was established. His work continued to inform later missionary endeavours in other parts of the world.

By the mid-1660s, there were approximately twelve villages and many converts. This was a time of some prosperity and Eliot was able, with backing from other colleagues, to establish, in conjunction with Harvard University, a college for the further education of Native Americans.

The Algonquians were not just one individual tribe but a collection of 24 small tribes with a common language, and the prominent tribe in the Roxbury area were the Wampanoag tribe. In 1621, Massasoit was the chief or sachem, who had greeted the first settlers to New England. The relationship between the first settlers and the native peoples had been wary, but during the first severe winter, the natives had helped with food and knowledge. Whilst Massasoit was alive the relationship with the settlers was relatively cordial. Sadly, as the numbers of new settlements grew and increasing areas of their territory were annexed, the relationship deteriorated. Despite having left England because of the prejudice shown to themselves, many of the newer settlers were equally as prejudiced towards the natives.

After the death of Massasoit in 1661 and the succession of his second son Metacom (also known as Philip) a war broke out between the Native Americans and two of the settlements in particular – the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Plymouth Colony – over the constant annexing of more land. Metacom rallied other tribes to his assistance but was killed in battle approximately a year later. During that year, the conflict – known as King Philip’s War – destroyed much of Eliot’s work, with the Christian communities he had founded amongst the Native Americans burnt down in the fighting, along with many (but happily not all) of the copies of the Bible in the Algonquian tongue.

When the fighting was over, Eliot once again began to walk the surrounding country to find and offer support to the Native Americans and their families. The Native Americans welcomed him and still esteemed his help and knowledge, but the mood of the settlers had turned against Eliot’s lifetime work, and he was never able entirely to rebuild his earlier success. He retired as the principal minister in Roxbury at the age of 82, but even in retirement, he continued to minister to and support the Native Americans, even taking young men into his own home so that they could continue their education.

Despite hardships and the grave disappointments he faced, Eliot retained to the end of his life his faith in a sovereign God whose missionary purposes could not be thwarted. He lived in Widford for fewer than six years, but it was here his baptismal vows were made; vows that would change his life, and the life of thousands across the seas. During his final illness, reflecting on his life, he reported, “My doings! Alas, they have been small and lean doings, and I’ll be the man to throw the first stone at them all.”

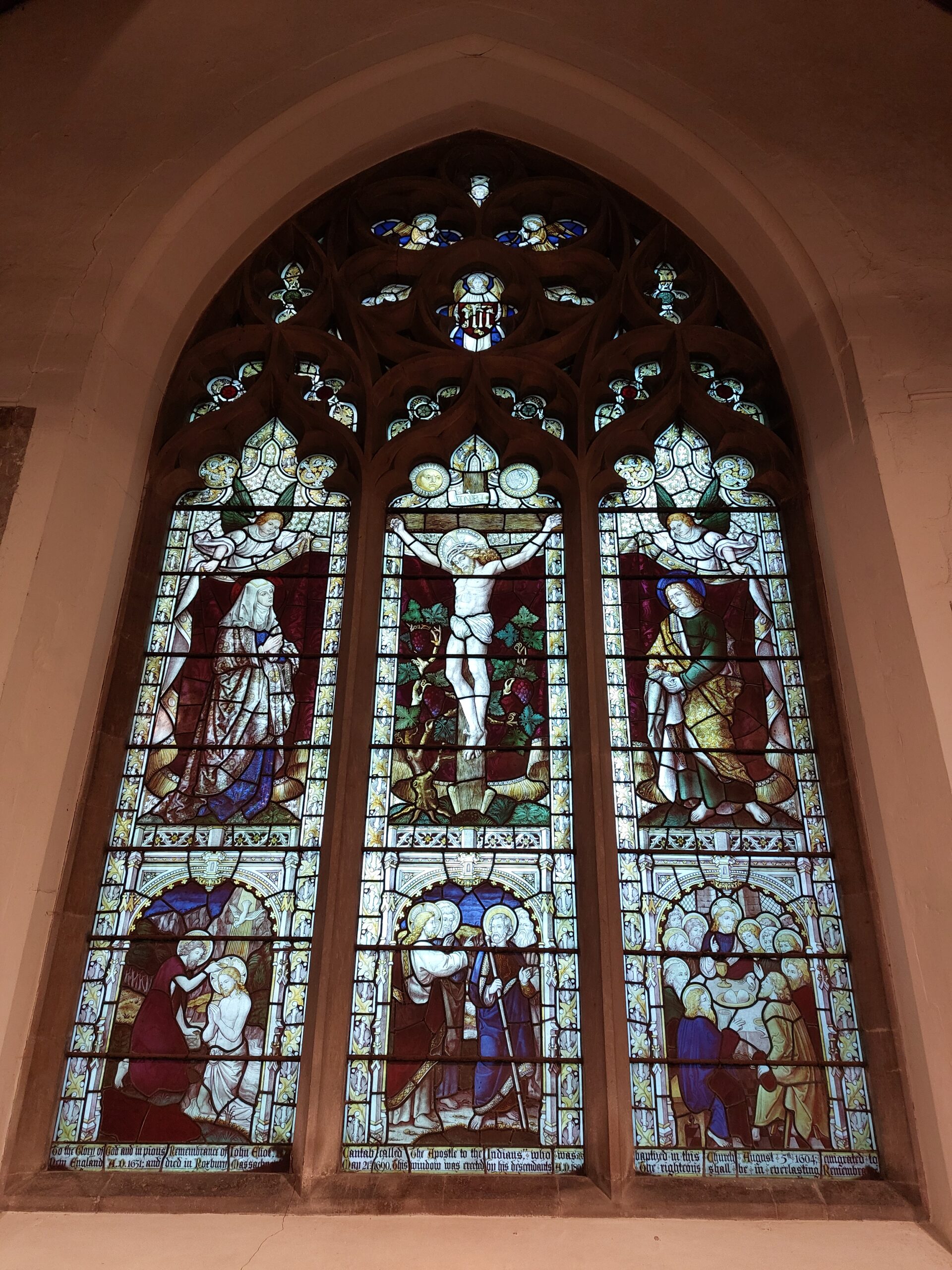

John Eliot died peacefully on 21st May 1690 after a long and adventurous life. His descendants donated the church’s east window in his memory in 1894.

The Wampanoag language, rightly called “Wôpanâak” has been recently revived and continues to be taught today among the surviving local indigenous people. This has been made possible by Eliot’s literary legacy – it was he who created the orthography and grammar and printed many translations, including the Bible.

With thanks to David Scott and Jill Buck and, from Massachusetts, Pastor Andrew Belli